Taking photos impairs memory

Attentional disengagement and cognitive offloading

Multiple studies have demonstrated the “photo-taking-impairment effect,” in which a person’s memory of objects they photographed was weaker than their memory of objects they didn’t photograph. This 2014 article by Linda A. Henkel provides early evidence in the context of a guided tour of an art museum: “If participants took a photo of each object as a whole, they remembered fewer objects and remembered fewer details about the objects and the objects’ locations in the museum than if they instead only observed the objects and did not photograph them.”

Interestingly, in the same study, the photo-taking-impairment effect did not surface when participants zoomed in on a specific part of the object, even for parts of the object they did not zoom in on. This motivated psychologists to develop theories and study the conditions under which the photo-taking-impairment effect occurs.

In this post, we’ll look at one of these papers: “Does taking multiple photos lead to a photo-taking-impairment effect?” by Julia S. Soares and Benjamin C. Storm, published in the Psychonomic Bulletin & Review in 2022. As its title suggests, the paper considers whether taking multiple photos leads to a photo-taking-impairment effect. On the surface, it seems that if someone takes multiple photos of an object, especially if those photos are different from each other, then they might remember it better because they’ve viewed the object in a more prolonged, deliberate manner.

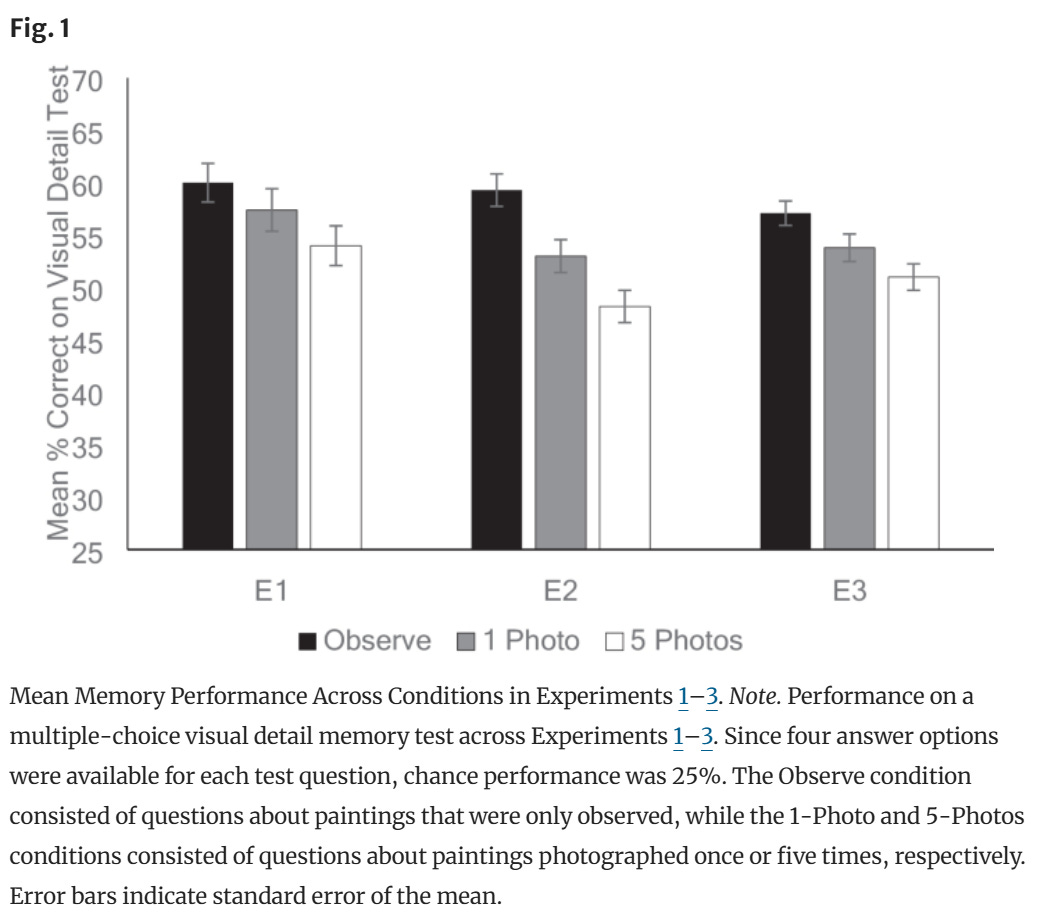

But the paper shows that this is not the case. In three separate experiments, participants who took one photo of an object scored higher on a memory test than participants who took five photos. Participants who didn’t take any photos, and only observed the object, scored highest. At the end of this post, we’ll discuss two potential explanations of the photo-taking-impairment effect.

Experiment 1

Participants were told that they would view some paintings, photograph some of them, and take a multiple-choice test at the end without access to the photos. There were 30 paintings, and each painting was on the computer screen for 20 seconds. Under each painting, there was one instruction for participants: just observe, take one photo, or take five photos. After viewing each painting, the participants were asked, “How likely (out of 100%) are you to correctly answer questions about the painting’s visual details?” And after viewing all 30 paintings, the participants were directed to play Tetris for five minutes. Finally, they took a 20-minute test containing 60 multiple-choice questions (two questions per painting) on visual details in the paintings (e.g., “What phase is the moon in Moon River by R. C. Gorman?”).

Based on participants’ performance on the multiple-choice questions, there was “a significant linear trend indicating that when more photos were taken, memory performance decreased” (see the three leftmost bars in the figure below). (As we’ll se, and as we can see in the same figure, the results from the other two experiments were consistent with this finding.)

Experiment 2

This was a between-subjects design version of Experiment 1 (which had a within-subjects design). More specifically, participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: just observe every painting, take one photo of each painting, or take five photos of each painting. After viewing the paintings, these participants took the same test as the participants in Experiment 1 did.

Again, the authors found that “when more photos were taken, average performance decreased.”

Experiment 3

This was similar to Experiment 2, with just one notable change: participants in the “5-photos” group were instructed, “Please take 5 different photos of each painting using the device provided. Try to make each photo different from the others.” (People who took 5 photos in Experiments 1 and 2 were not told to take different photos; many took five nearly identical photos.)

For the third time, there was “a linear trend such that when more photos were taken, average performance decreased.” The authors also conducted a meta-analysis on the findings in all three experiments, and found a “significant and moderately large” effect size for the photo-taking-impairment effect.

Discussion

As mentioned earlier, it might sound plausible that taking multiple different photos of the same object reduces the photo-taking-impairment effect. But in Experiment 3, the opposite was true: the photo-taking-impairment effect was more pronounced for the “5-photos” group than the “1-photo” group.

According to the authors, there are two major theoretical accounts of the photo-taking-impairment effect: attentional disengagement and cognitive offloading.

Attentional disengagement occurs when photo-takers “disconnect from the scene, thereby preventing them from fully encoding or attending to photographed objects.” They focus more on the act of photo-taking, especially if they’re taking multiple photos, than the object itself. In a lecture, if a student spends too much attention on taking detailed notes, they might not remember the actual content of the lecture.

Cognitive offloading occurs when “photo-takers believe that the objects they photograph are saved by the camera, reducing the need to remember those objects internally.” Taking multiple photos could strengthen this belief, thus amplifying the photo-taking-impairment effect. Since participants were told that they would not have access to the photos during the test, my hunch is that cognitive offloading is largely a subconscious phenomenon. Of course, taking a photo allows us to consult it later, but if we never consult it, we might remember less than if we hadn’t taken the photo.

Near the end of the paper, the authors note, “Future work should examine the effects of other common photo-taking behaviors like using filters, using camera modes like panorama or portrait mode, or making other adjustments to brightness or color balance.” It’d be interesting, and amusing, if some convoluted way of taking photos (e.g., decrease brightness, then zoom in and increase brightness) results in improved memory of the object.